Qumra: Doha Film Institute’s platform for emerging filmmakers

The 11th edition of the event included talks by filmmakers as diverse as Brazilian director Walter Salles, Filipino director Lav Diaz, Hong Kong director Johnnie To and Iranian-French cinematographer Darius Khondji.

Qumra 2025 was held from April 4 to 9.

Qumra 2025 was held from April 4 to 9.In its 11th year, Qumra, the Doha Film Institute’s (DFI) platform for emerging voices in cinema, has become bigger, and is well on track to do what it set out to: to become a springboard for local talent in the region, nurturing and mentoring their projects from a nascent stage to completion.

It is also a place where celebrated filmmakers are invited to share their experiences and best practices in a set of curated masterclasses. These two-hour long sessions are almost like a guided tour of the art and craft of these filmmakers, beginning at their beginning (the first question invariably being ‘what drew you to cinema’) to where they are now, and their significant cinematic moments in between.

These filmmakers also provide one-on-one mentorship to the selected projects (this year’s funding has gone to 49 projects), something that has deep value for those beginning their own careers in cinema. The making of a film can be an all-consuming, long-drawn affair, where expert hand-holding and guidance can make all the difference, and like all cinema labs, this DFI flagship programme — a talent incubator — is meant to provide exactly that.

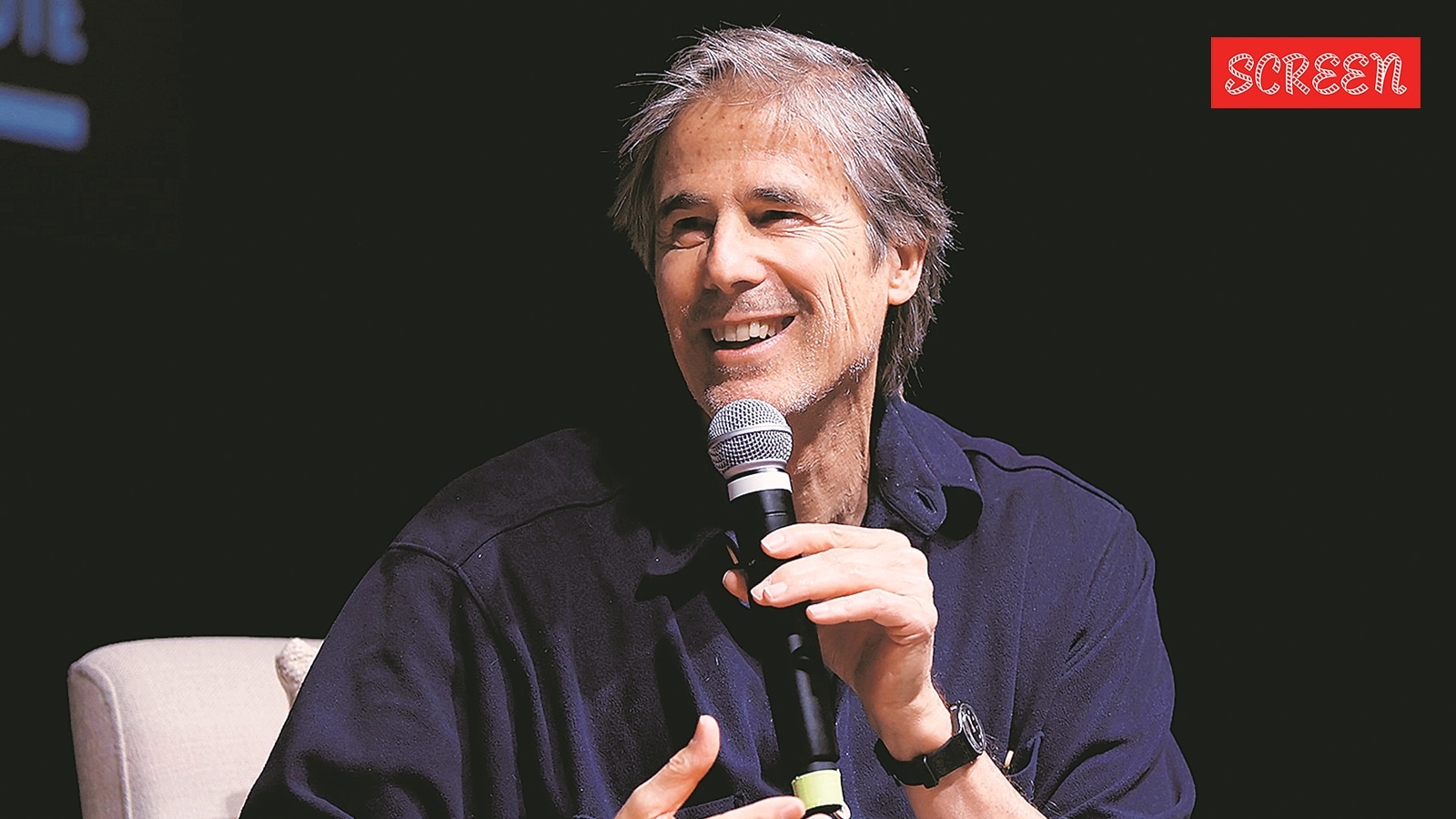

The highlight of Qumra 2025 was the masterclass with Walter Salles.

The highlight of Qumra 2025 was the masterclass with Walter Salles.

This year, the Qumra ‘masters’ included Brazilian director Walter Salles (I’m Still Here, Motorcycle Diaries), Filipino Lav Diaz ( From What Is Before, The Woman Who Left), Hong Kong director Johnnie To (Election, Breaking News), Iranian-French cinematographer Darius Khondji (Amour, Se7en), and Mexican costume designer Anna Terrazas (Roma, Bardo).

The highlight this year was the masterclass with Salles, whose I’m Still Here received the Best International Film at the Oscars this year. It was anchored by a tremendous performance from Fernanda Torres as Eunice Paiva, who waged a long, lonely battle to understand the reasons behind the disappearance of her husband Rubens Paiva during the dictatorship in Brazil.

Salles, who has been on the move since the film’s premiere at the Venice International Film Festival, touched down in Qumra for a mere 48 hours. Through the masterclass, the grounded warmth of the director, fighting jet-lag, came through, as he emphasised the importance of finding humanity in the moving image. “When you see everything, it is television: when there is something left to find, and you are invited to complete a dialogue, you are in cinema,” he said.

A director who layers a strong documentary, observational approach in his fiction, Salles understands the joy of finding something unexpected while filming. In I’m Still Here, which is one of the most vivid documents of the military rule in Brazil, it is the ‘presence of absence’, which is the most striking feature: in all the frames, you see absence; it is show, not tell.

That same ability of being alive to the moment, and accessible, is evident in the post-masterclass conversations he has with the visiting press. I ask him if he is aware of similar situations in India, caused by the men who have disappeared during the conflict in Kashmir, with their families left to cope with that absence, without having the resources to come out of the permanent hole it leaves in the lives of their loved ones, as reflected in a clutch of films. “I do follow Indian cinema (even if not specifically films with that subject),” he says, and speaks of the Indian film that he has been moved by the most in recent years, Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine As Light, which, he says is a “complete masterpiece”.

Part of the enjoyment of the session with Lav Diaz was the way he peppered it with colourful invective, fearlessly calling out political shenanigans happening in the world around us, even as he gave us a run-through of his work, popularly known as ‘slow cinema’: his films are famously long, ranging from four to nine hours. He’s always been dismissive of that label, calling it his desire to capture life itself. “In Indian cinema, my heroes are Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak,” he says, “the value for me to convert even one person towards my perspective is more important than ten thousand people lining up for my films.”

DFI CEO Fatma Hassan Alremaihi

DFI CEO Fatma Hassan Alremaihi

The cinema of Johnnie To, with his signature stamp of highly-stylised violence, is a visual feast, and in our brief chat, he speaks of his admiration of Bruce Lee in that OG martial arts blockbuster Enter The Dragon (1973), but doesn’t admit to any influence. However, he has had a vast sphere of influence, starting with Quentin Tarantino, but is not sure of how long his brand of Hong Kong cinema will last.

As DFI CEO Fatma Hassan Alremaihi put it eloquently in her opening speech, cinema and storytelling is more important than ever before to heal the wounds inflicted by global conflict, especially in the backdrop of Gaza. As Qumra heads into its next edition, there is excitement surrounding one of Qatar’s first narrative features, filmmaker AJ Al-Thani’s Sari and Amira, an adventure revolving around bandits and hidden treasure. The film could be one itself.

Must Read

Buzzing Now

Apr 22: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05